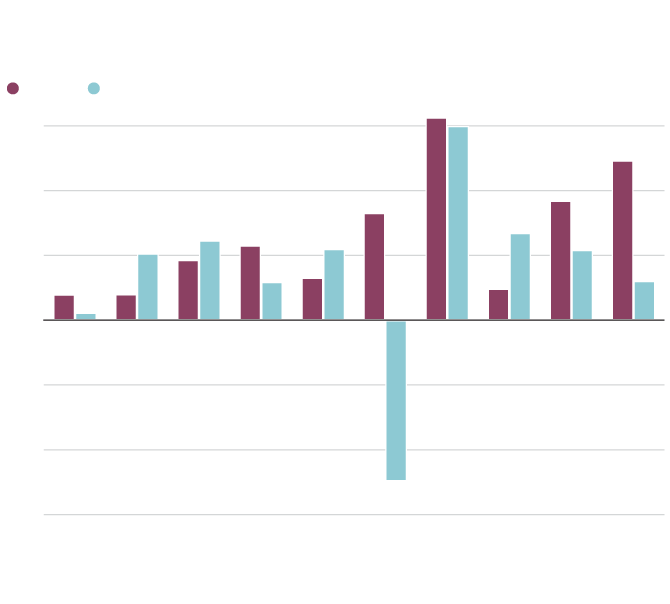

Public vs. private employment growth

2024 = last 12 months as of March

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, source: statistics canada

Public vs. private employment growth

2024 = last 12 months as of March

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, source: statistics canada

In 2015,

Prime Minister

Justin Trudeau

inherited an economy

weakened by the

previous year’s oil

price correction

Percentage change in public

vs. private employment growth

(2024=last 12 months as of March)

Over the

past year public

sector employment

growth has far outpaced

that of the private sector,

a trend that’s intensified

in the past few

months.

2018-19:

Before the pandemic

the private sector had

begun to recover, but

public sector employment

was building too, partly

reflecting hiring at

the federal level.

2020–21:

COVID–19 severely

affected business

employment, as governments

ramped up emergency

spending programs. In 2021,

both public and private

sectors rebounded with

strong growth.

the globe and mail,

Source: statistics canada

photograph: Sean Kilpatrick/cp

In the final weeks of the 2015 federal election that would sweep Justin Trudeau to power, the Liberal leader penned an open letter to Canada’s federal civil servants promising that if he were elected, government workers would be a lot better off than they were under the last guy. “I have a fundamentally different view than Stephen Harper of our public service,” he wrote. “Where he sees an adversary, I see a partner.”

By the time throngs of cheering, selfie-snapping bureaucrats mobbed Mr. Trudeau days after he was sworn in as prime minister, it was clear the dynamic between the federal government and its hundreds of thousands of employees was about to shift dramatically after years of acrimony and cuts.

Nine years and one global pandemic later, the full extent of that change has become starkly apparent, and it is reshaping the Canadian economy. The number of workers in Canada’s public sector has soared, led by the swelling ranks of the federal civil service but including growth at all levels of government. At the same time, Canada’s private-sector employment has wilted under high interest rates and a pullback in investment.

It’s a picture that economists warn is not sustainable in the long run, neither from the perspective of federal and provincial finances nor for the state of Canada’s economy. It’s not only that public-sector hiring is masking how weak the country’s job market really is, they argue, and may have compelled the Bank of Canada to maintain interest rates at a higher level than is warranted. But also, the public sector’s ever-expanding role in the economy, which appears to stand in contrast to other countries – the U.S. in particular – may be part of why productivity and innovation in Canada are lagging.

And it raises questions about whether Canadians are getting value for the growing ranks of public servants they’re footing the bill for. An analysis of the federal government’s own report cards on performance suggests that isn’t always the case.

“The growth in the public sector we’ve seen over the last several years doesn’t seem to be compatible at all with expenditure restraint, and service levels have clearly not kept pace with that growth,” said Yves Giroux, Canada’s Parliamentary Budget Officer. “It’s very worrying because it’s taxpayers’ money and it’s services to Canadians that impact on peoples’ lives.”

Now, as the Trudeau government prepares to release its 2024 budget on April 16, on the heels of a string of red-ink stained provincial budgets, there are signs the public-sector expansion itself is running out of steam, leaving Canada facing a conundrum: If private-sector job growth is in the doldrums, what happens to the economy if the public-sector joins it?

Just how much has the federal civil service grown since 2015? According to the Treasury Board Secretariat, the federal government has added 100,000 employees since 2015, with nearly 70 per cent of that growth occurring since 2019. But it’s only when accounting for the change in Canada’s population over time that the recent surge can be put into perspective.

“Even though the population in Canada has exploded in the last few years, the number of public servants has grown even faster,” said Gabriel Giguère, a public policy analyst with MEI. “Under Justin Trudeau we’re seeing a government that doesn’t want to manage this growth and there’s a direct impact on our pocket.”

Not everyone agrees with this interpretation. “The government has not ballooned out of control, all that’s happened is the Liberals rehired some of the 45,000 jobs that Stephen Harper cut in four years,” said Chris Aylward, national president of the Public Service Alliance of Canada, the largest federal union. “We’re at the same staffing levels we were at in 2010 in correlation to the population.”

How can both be right? Because the federal civil service is something of a black box when it comes to measuring its size. The Treasury Board numbers count individual employees in its pay system, while departments report staffing as full-time equivalents, and the two measures don’t necessarily capture all the same facets of government employment.

But it’s also worth noting that regardless of how employment is counted, the peak under Mr. Harper in 2010 came amid a surge in deficit-fuelled stimulus spending aimed at blunting the pain of the deep and prolonged 2008-09 recession, and in absolute terms federal employment under Mr. Harper more or less came full circle to where it began.

Some of the public-sector growth can be explained by simple demographics and the pandemic response, but not all of it, as this chart of the top 20 fastest growing federal departments shows.

But ESDC also administers benefits such as regular Employment Insurance, the Canada Pension Plan, Old Age Security and disability benefits, and half a million people in Canada now turn 65 each year.

“The aging of the population is a huge part of this,” said Tammy Schirle, professor of economics at Wilfrid Laurier University, pointing to laborious tasks such as processing applications for CPP and disability benefits, with each file handled by hand. “It’s time intensive, you’re answering people’s questions, dealing with the crisis in their lives, and you can’t automate all of this, especially when it comes to seniors benefits.”

Yet at the same time, overall program spending has soared under the Trudeau government, and continues at a pace far ahead of its prepandemic levels relative to GDP.

The government has repeatedly missed its deficit targets and TD Bank said in a recent prebudget analysis that Ottawa may once again fall short of its pledge to hold the deficit at or below $40-billion this fiscal year. The bank said the deficit was on track to be closer to $55-billion.

Feeding into that is the bill for the federal government’s swelling ranks. Personnel costs are the government’s single largest expense and Mr. Giroux said compensation is on track to climb 6.6 per cent this year compared with the previous year.

It’s not just the federal government that has been snapping up employees, of course. Across Canada, provincial governments also ramped up their hiring after the start of the pandemic, to the point that several provinces have added as many, if not more, public-sector workers than jobs in the private sector, including self-employed, over the past four years.

A big driver at the provincial level is health care, the largest of the public-sector industries. Looking below the headline job numbers, Dr. Schirle found a significant shift from casual and part-time work to full-time jobs in that sector since the pandemic, reflecting, “a real structural change in the employment contracts and how we organize people in some of these sectors.”

But the fastest rate of growth in the public sector has been public-administration jobs, and payroll data from Statistics Canada show that of the federal, provincial and municipal levels of government, Ottawa has led the way by far.

“There’s been a fundamental change to public management that’s led to an explosion of public-sector employment, and that’s helped make it look like there’s job growth across the broader economy,” said Ben Eisen, senior fellow in fiscal and provincial prosperity studies at the Fraser Institute. “For Canada to prosper and have a sustainable recovery that drives growth in the long term, there has to be a dynamic and robust private sector. It can’t be driven permanently by growth in the size of government.”

Two years into the pandemic, as the public sector outpaced the private sector in creating jobs, concerns about the trend could fairly be countered by pointing to the festering wounds inflicted on the economy by the lingering health crisis. Far more business sector jobs had been lost, so it made sense they would take longer to recover. Meanwhile, governments had massively ramped up emergency benefit programs, and sectors like health care had to staff up.

But the world is now four years removed from the darkest days of the pandemic, and it’s harder to justify the public sector being a primary driver of Canada’s job market.

“One of the reasons we have avoided a recession is that public-sector support from the pandemic and the budgetary decisions made during the pandemic are still very much feeding through and supporting the economy,” said Stephen Brown, deputy chief North America economist at Capital Economics. Government spending now accounts for the largest share of GDP in 14 years, apart from the early stages of the pandemic. “It would be one thing if we were in a recession and we increased government spending to get out, but that isn’t what’s going on here,” he said.

What worries economists is the possibility government hiring and spending is contributing to weakness in the private sector. That could happen in a number of ways.

For one, the public sector may have hoovered up employees who would otherwise be available to businesses, attracting them with the higher pay that is often available in government jobs, not to mention lucrative pensions and job security. “The government provides attractive compensation packages and it may be crowding out employees that other sectors would also need,” said Mr. Giroux.

That’s less of a concern now than it was when the job market was extremely tight in 2022 and early 2023, according to Philip Cross, senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, though he notes that throughout the pandemic, and even now, public administration and education have the lowest vacancy rates of all sectors.

“Vacancy rates suggest the public sector is overpaid because they’ve had no trouble attracting workers, whereas private employers are having trouble,” he said, adding that health care is the public sector exception, since low pay is making it hard for the industry to fill jobs.

Canada’s weak productivity levels may also partly reflect the public sector’s growing share of the economy and job market. Productivity is lower in general in the public sector, so to the extent that more of the economy is dependent on government output, that will weigh on productivity.

“The challenge in a lot of public sector jobs is there is no market for the services they’re providing, and so whether somebody takes two days to write a briefing note or two weeks, it’s still roughly the same output,” said Stephen Tapp, chief economist at the Canadian Chamber of Commerce. “How do you judge quality?”

Bank of Canada Governor Tiff Macklem and Deputy Governor Carolyn Rogers attend a news conference in Ottawa on April 10.Adrian Wyld/The Canadian Press

Related to both of these forces is the possible impact strong government hiring has had on monetary policy. Well into 2023 the Bank of Canada pointed to elevated job vacancies as evidence Canada’s economy was overheated. “Because government hasn’t rolled back some of that employment, the Bank of Canada has had to keep interest rates higher than it would have otherwise,” he said.

For its part the Bank of Canada looks “at the labour market in its totality,” said Governor Tiff Macklem in an interview, adding that over the past year unemployment has risen and wage pressures have eased. “Things are moving in the right direction.”

Public sectors have grown in other countries. What sets Canada apart is the degree to which that has happened. Economists are quick to note that drawing international comparisons is difficult because of the make up of job markets. “The way things are funded and structured across different countries makes it extremely hard to make comparisons,” said Dr. Schirle. The gulf between how health care is funded and administered in Canada and the U.S. is a case in point.

That said, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development tracks general government employment as a share of the job market every two years. The latest available data, released last year, are from 2021, but the trajectory of Canada stands in stark contrast to other developed economies, and could see this country overtake France in terms of bureaucratic bulk.

One upside of all this could be greater overall wage equality, according to David Macdonald, senior economist with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. In a recent report, he found the pay gap between men and women in the private sector is twice as wide as in the public sector, after adjusting for factors such as age, occupation, industry and tenure. However he also notes that since early 2021 private-sector wages have done a better job at keeping pace with inflation.

Still, for Mr. Cross, the economy’s growing reliance on the public sector for jobs reflects the sorry state of the Canadian economy and should spark an existential debate about the plight of private business.

“At this point we have to look as a nation and ask ourselves, ‘Do we even believe in capitalism any more? Do we even believe in the private sector?’” he said. “If we do, we have to stop doing the things that discourage risk taking in this country.”

Paramedics wheel a patient into the emergency department at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto on Jan. 13, 2021. Between 2017 and 2022, Canada experienced a drop in health care satisfaction from 69 to 56 per cent.Cole Burston/The Canadian Press

While economists grapple with what an inflated public sector means for the economy, it’s worth asking if more civil servants at least means better and faster government services.

One way to gauge that is through surveys, which doesn’t leave Canada looking good relative to its international peers. The OECD polls residents at its member countries on their satisfaction with public services such as health care and education, and between 2017 and 2022, Canada experienced the largest decline in satisfaction among G7 countries for education (from 73 to 67 per cent) while the drop in health care satisfaction matched that of the United Kingdom, but to the lowest level in the G7 (from 69 to 56 per cent).

Canadians are certainly finding less to like with the services they’re receiving from their provincial governments, according to surveys conducted each quarter by the Angus Reid Institute. The share of respondents who said their provincial government had done a “good” or “very good” job fell overall from close to half in the first quarter of 2019 to 30 per cent at the end of 2023. Both B.C. and Quebec, two provinces that have seen public-sector job growth rise particularly quickly, registered some of the worst declines.

Another way to measure performance is to go to the source. Each year federal departments release self-assessed report cards scoring themselves on how they’ve performed against a dizzying, and often shifting, number of targets.

In March, 2023, the Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) reviewed four years of results reports to see how the government measured up against nearly 3,000 performance targets it had set for itself. The assessments weren’t promising. For fiscal 2021-22, roughly 25 per cent of targets were not met, up from 20 per cent in 2018-19. But that didn’t capture the full scale of the performance shortfall. One-tenth of performance targets included no information on results, while another one-third stated results would be achieved at some point in the future.

“In some areas service levels have improved compared to catastrophic levels if one thinks about passport delays, but over all, less than half of targets are met in any given year,” said Mr. Giroux.

Drilling down into individual department reports presents a thoroughly muddy picture of performance.

ESDC sets a goal that 90 per cent of CPP benefits are paid within the first month someone becomes entitled to them, and in 2017-18 it exceeded that target with a 95.8-per-cent rate. In 2022-23 the department came close to matching that performance, but on another metric – of whether calls are answered within 10 minutes – its performance fell from 69.8 per cent to just 6 per cent over that same time period, even though that coincided with a 50-per-cent jump in employment.

Meanwhile, CRA spokesperson Nina Ioussoupova responded to questions about the agency’s performance by noting that it exceeded 71 per cent of its service standard targets in 2022-23, up from 57.6 per cent in 2020-21. However that was still shy of the agency’s 75-per-cent target.

Canada Revenue Agency national headquarters in Ottawa in April 2023. The CRA added more than 15,000 jobs between 2019 and last year, a 34 per cent increase, as Ottawa ramped up its emergency benefits programs for individuals and businesses.BLAIR GABLE/Reuters

This all leaves Canadians to puzzle over whether they’re getting value-for-money from their government, said David-Alexandre Brassard, chief economist with CPA Canada. But the lack of transparent metrics to justify staffing levels also exposes governments to accusations of overspending and waste by their critics. He points to four decades of wild swings in federal hiring, from periods of overstaffing to eras of deep cuts, that he said are driven more by ideology than measurable requirements.

“If you’ve got clear business cases that are tied to service delivery, you can better defend your hiring decisions,” he said. “It would elevate the discourse around the public sector, which right now is dumb, with Liberals saying there’s nothing wrong with the size of the public sector and the Conservatives saying nobody is working and money is being thrown out the door. Both positions are deeply simplistic.”

When Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland rises to deliver the budget next week, few economists expect fireworks, but neither do they expect public-sector growth to continue the way it has.

Some belt tightening is already under way, set in motion by last year’s budget, which pledged to cut spending by $15.4-billion over five years. That said, talk of reductions has morphed into what the government calls refocused spending, and Treasury Board president Anita Anand has said she doesn’t expect involuntary layoffs will be necessary.

As it stands the number of planned full-time equivalents in the federal government is expected to have jumped by another 7,500 this fiscal year, the PBO found when it analyzed the latest departmental plans. Those plans do lay out reductions in the years ahead, but that’s what past plans showed too.

“Departmental plans repeatedly show there will be reductions in FTEs but when the plans are implemented there’s no decrease, only increases,” said Mr. Giroux. The apparent failure to accurately plan comes down to the complex way departments must report resources for sunsetting, or time-limited spending programs that may or may not be renewed. That, combined with the Trudeau government’s penchant for launching new programs – pharmacare, dental care, a national school lunch program – makes it nearly impossible to square talk of spending reductions with a trimmer civil service.

So far, there’s little evidence of actual job losses. Ms. Ioussoupova at CRA said the agency found savings last year by getting rid of programs and operations that offered lower value or were redundant. She said that while “a small number of employees may change roles, we can confirm that no job loss is expected” as a result of the 2023 budget measures.

Both CRA and ESDC also said in statements that services won’t be affected by spending reductions.

Still, unions representing federal workers are bracing for tougher times. In its prebudget submission the Public Service Alliance of Canada urged Ottawa to “pause” any cuts until it reviews staffing and service needs across the government.

“I don’t care what the government says, if you cut the public service, you’re cutting services to Canadians,” said PSAC’s Mr. Aylward, who argued that a job left open owing to attrition is still a job loss.

Economists say Ottawa’s relatively small deficit, equal to 1.5 per cent of GDP, means it doesn’t face a fiscal emergency. Even so, they add, the hiring spree should not continue.

“For the next five to 10 years government finances should be reined in,” said Doug Porter, chief economist at Bank of Montreal. “There’s no emergency but the medium to longer-term goal should be to strengthen government finances to leave us in better shape for the next real emergency.”

As for the provinces, fiscal scars are forming. Collectively, provincial net debt is on track for the largest one-year increase on record, at $65-billion, Mr. Porter said. That’s leading to talk of austerity in some quarters.

In mid-March, after the Quebec budget was tabled featuring a much larger-than-expected $11-billion deficit, Premier François Legault vowed to pull back spending, beginning with a slimmed down public sector. “We are going to review spending to reduce bureaucracy, to be able to remove spending that is not effective,” he told reporters during a press conference.

That plan won’t attract the kind of bureaucrat groupies that encircled Mr. Trudeau nine years ago, but if it leads to fiscal stability and a revived economy, other leaders are sure to follow him.

With a report from Mark Rendell